By Guillermo Moreno-Sanz

Dr. Moreno-Sanz has authored more than 30 scientific articles and 3 patents describing the role of the endocannabinoid system in pain perception. Graduated in Biochemistry and Organic Chemistry from the University of Zaragoza, he obtained his PhD in Neuroscience from the Complutense University of Madrid, in Spain. He gained extensive international experience with long-term fellowships in the Netherlands, Italy, and the United States, developing most of his academic career at the University of California, Irvine, where he discovered a new class of cannabinoid analgesic with high clinical potential. In 2017, he acted as a consultant to the National Academies of Sciences of the United States in the preparation of the report "The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids" and later founded Abagune Research to offer scientific advice and R&D solutions to the international cannabis industry. In 2020 he assumes the scientific and medical direction of Khiron Life Sciences in Europe.

Most patients who resort to start a treatment with cannabis or its derivatives do so to alleviate symptoms associated with chronic pain. This is a constant that is repeated in all the studies carried out in those countries with medical cannabis access programs, only recently altered by the growing number of patients who use cannabis to alleviate disorders related to anxiety and stress.

For this reason, it is so shocking for those demanding the regulation of the therapeutic use of cannabis that leading medical associations, such as the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), advise against the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain based on the existing (or non-existent) evidence. This debate on the existence or non-existence of sufficient scientific evidence to recommend the therapeutic use of cannabis has permeated the congressional subcommittee currently preparing a proposal to regulate the medicinal use of cannabis in Spain which, moving away from its mandate to "analyze experiences of regulation of cannabis for medicinal use", seems to be getting into troubled waters in which one can easily get lost.(1)

But, what do we mean when we talk about evidence-based medicine?

When a physician makes a therapeutic decision, it is usually based on his or her own clinical experience, coupled with the best available objective data, and always considering patients' preferences. This scientific data on which to base a therapeutic intervention is what we refer to as medical evidence. Although it sounds logical and well-established, evidence-based medicine is relatively young, having been developed in the 1970s with the rise of clinical trials for the approval and marketing of drugs. One of the pioneers of evidence-based medicine was the British clinical epidemiologist Archie Cochrane, who defined three concepts related to treatment decision-making: efficacy, effectiveness, and efficiency. Efficacy determines whether a treatment does more good than harm under controlled conditions, such as those of a clinical trial (can it work?). Effectiveness assesses whether a treatment does more good than harm when administered under normal conditions of healthcare practice (does it work in the real world?). Efficiency measures the effect of an intervention in relation to the resources it requires (is it worth it?).(2) However, it was not until the early 1990s that a change in the model of medical education and practice was initiated, the ideology of the Evidence-Based Medicine movement was formulated, and the methodologies used to determine the quality of scientific evidence were carved in stone.(3) Thus, in 1993, the non-profit organization Cochrane was founded to, through the work of volunteer researchers from all over the world, rigorously and systematically review health interventions to facilitate decision-making by health professionals, patients and health policy makers in accordance with the principles of evidence-based medicine.

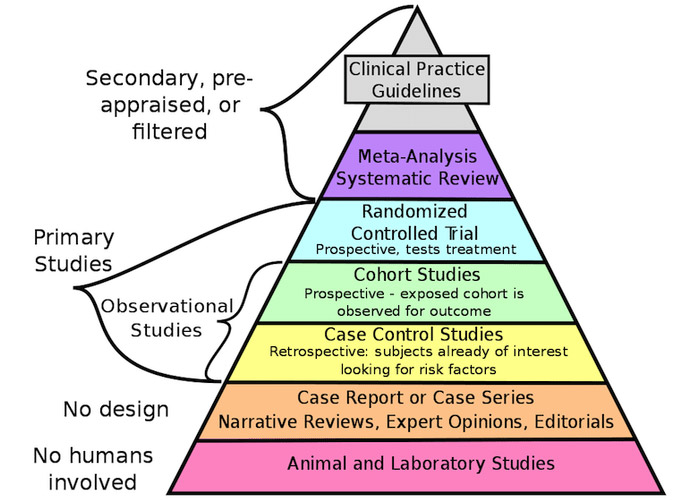

Figure caption: Pyramid of the quality of scientific evidence (based on reference 3).

Top-notch scientific evidence wanted!

As can be seen in the "pyramid of the quality of scientific evidence" (see figure based on reference 3), data considered to be of the highest quality come from the results of "experimental studies" such as randomized clinical trials (RCTs), meta-analyses and systematic reviews. In second place comes data from "observational studies", such as cohort studies or clinical cases, which can be very varied in their design and typology. And at the bottom of the pyramid we find very-low quality clinical evidence to inform a therapeutic option, such as narrative reviews, expert opinions and animal studies.

RCTs are investigations conducted in humans in progressive phases, first in healthy volunteers and then in patients, whose goal is to determine the efficacy (can it work?) of a drug or medical device for a specific health condition or "indication". These studies are part of the process of registering and obtaining the necessary authorization to market the product for that indication. This process is extremely costly, both in terms of time and financial resources, and is usually applied to new drugs protected by intellectual property that allows the sponsor of the RCT to recover the investment through years of sales of the product. This is one of the main reasons why cannabis derivatives, which are difficult to patent and are marketed as magistral formulations, are not attractive for traditional drug development through the classical pharmaceutical route. RCTs are also essential to establish the safety of a new drug. Of particular relevance are "first-in-human" trials, in which drugs whose toxicity has been ruled out in cells and animals are administered for the first time to healthy humans. With more than 5000 years of use by humans, cannabis has a relatively safe pharmacological profile, with generally mild and mitigable side effects. Meta-analyses are statistical tools that allow the results of different studies to be combined in order to analyze the same variables and, therefore, can provide more information or have a greater scope than each of the individual clinical studies from which the data were obtained. Finally, systematic reviews provide a structured summary of the existing evidence published in different formats using a rigorous methodology.

On the other hand, observational studies are those in which the researchers do not interfere with what happens in routine clinical practice. That is, they limit themselves to observing and collecting information, but they cannot control any variable, determine doses or administration times, randomize patients, or assign them to a placebo group. However, these types of studies have gained relevance in recent years due to their ability to collect real-world evidence or data, as opposed to the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria of RCTs, which often result in study participants being unrepresentative of broader clinical populations. Therefore, real-world studies are increasingly considered to be able to provide complementary information to that obtained in RCTs, collected through electronic medical records over long periods of time, about the long-term safety and effectiveness of a treatment (does it work in the real world?) in large, heterogeneous populations, as well as prescribing patterns or medical and economic implications of its use.(4)

What about medical cannabis?

As we have seen, the evidence considered to be of high quality according to the evidence-based medicine law tables comes from RCTs and their meta-analyses. To date, some sixty RCTs have been published investigating the use of cannabinoids in the treatment of pain, with considerable heterogeneity in terms of population size, indication, presentation (from cannabis flowers for inhalation to oral synthetic THC), doses, ratios of THC and CBD, route of administration, duration of treatment (from a few hours to several months) and outcomes measured so that, as might be expected, the results obtained are contradictory. In an effort to consolidate these results, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of these available data began to emerge. Between 2010 and 2019, 57 studies of this type were published only to intensify the debate due to their wide range of conclusions, ranging from those that find clear evidence of efficacy to those that affirm just the opposite. It should be kept in mind that most of the RCTs aimed at marketing the two cannabis or cannabinoid-based authorized medications, Sativex and Epidiolex, did not seek to characterize these products in chronic pain populations, but rather in multiple sclerosis and refractory pediatric epilepsy, respectively. At the same time, those countries where access to cannabis for therapeutic use is regulated are beginning to accumulate real-world evidence suggesting that chronic pain patients see their quality of life markedly improved by including medical cannabis preparations in their treatment regimen. Based on these findings and in contrast to the IASP statement, the European Pain Federation recommends considering medical cannabis as a third-line therapy for chronic neuropathic pain while, for all other cases of chronic pain, the use of cannabis derivatives should be considered as an individual therapeutic trial.(1) This means that, if approved treatments have failed, and after careful analysis and multidisciplinary assessment, a physician should be able to prescribe medical cannabis to their patients if he or she considers that they could benefit from the treatment. It seems that, little by little, and thanks to the accumulation of real-world evidence from the thousands of patients already benefiting from treatment with cannabis derivatives, Cochrane's questions are getting answered. Soon the question will not be whether medical cannabis is effective (not efficacious) but whether it is efficient. Because, to close the circle of access to medical cannabis, and avoid the threats of the black market or recreational regulation, it will be necessary for the cost of treatment to be covered or subsidized for those patients who need it. As it should be.

References:

1. Eisenberg E, Morlion B, Brill S, Häuser W. Medicinal cannabis for chronic pain: The bermuda triangle of low-quality studies, countless meta-analyses and conflicting recommendations. Eur J Pain. 2022 Apr 6;

2. Haynes B. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of healthcareinterventions is evolving. BMJ. 1999 Sep 11;319(7211):652–3.

3. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992 Nov 4;268(17):2420–5.

4. Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, Meizinger C, Skolnik NS. Interpretation and Impact of Real-World Clinical Data for the Practicing Clinician. Adv Ther. 2018 Nov 1;35(11):1763–74.